Dan’s friend Alex Goldmark insists that cheap vodka makes his face turn red; Dan doesn’t believe him, because Dan thinks all vodka is the same. We team up with NPR’s Planet Money, where Alex happens to be the senior supervising producer, to settle this debate once and for all. Along the way we visit a vodka distillery, learn about the origins of Grey Goose, and make our own vodka. Then these two guys walk into a bar, and try to cause an allergic reaction.

This episode contains explicit language.

Interstitial music in this episode by Black Label Music:

- "Still In Love With You" by Stephen Clinton Sullivan

- "Private Detective" by Cullen Fitzpatrick

- "On The Floor" by Cullen Fitzpatrick

- "A Call To Action" by Cullen Fitzpatrick

- "New Old" by JT Bates

Photo courtesy of Dan Pashman

View Transcript

Dan Pashman: Quick heads up, there is a bit of explicit language in this episode.

Dan Pashman: A while back, before COVID I went to a bar called O’Keefes, it’s a standard Irish bar in Brooklyn. I was there with my friend, Alex Goldmark.

Alex Goldmark: Former friend, because you, basically, picked an argument with me.

Dan Pashman: Yeah, you're right.

Alex Goldmark: I am telling you it is a real thing that happens, just about every time.

Dan Pashman: So wait, you're telling me when you drink cheap vodka you have an allergic reaction, but when you drink expensive vodka, you are fine?

Alex Goldmark: I am allergic to cheap vodka, that is my claim. When I drink cheap vodka, my face turns red, it gets a little hard to breathe. Like just a little. It's not like it's gonna kill me.

Dan Pashman: I don't buy it.

Alex Goldmark: You doubted my own personal claims about my own personal health.

Dan Pashman: Yeah, I know, Alex. Look, no offense, but I'm just really skeptical. I mean, vodkas are pretty much all the same. In fact, I think they have to be. And anyone who says otherwise, is falling for one of the greatest sales jobs of all time.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: This is The Sporkful, it’s not for foodies it’s for eaters, I’m Dan Pashman. Each week on our show we obsess about food to learn more about people. I broke the big news last week. We are about to launch a huge series that’s been in the works for three years. I’m setting out to invent a new pasta shape, actually get it made, and actually sell it. We’ll tell the story of this quest in a five-part series we’re calling Mission: ImPASTAble. And guess what? It launches in one week. We shared the trailer in last week’s show, check it out if you missed it.

Dan Pashman: This week we’re sharing one of our all time favorite Sporkful episodes, which first ran three years ago. So before COVID. It’s a special collaboration with the podcast Planet Money. We hope you like it, and get psyched for Mission: ImPASTAble, launching in just one week!

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Now, to the task at hand and I'm very excited because I have a co-host today, my old friend Alex Goldmark from Planet Money. Hey Alex.

Alex Goldmark: It's honor to be here.

Dan Pashman: So we go back, Alex. I was actually counting the years. We've worked together at so many different jobs. I've lost count of that but I know that we worked together in 2004.

Alex Goldmark: Yeah, two different radio stations. One of which is already completely out of business.

[LAUGHING]

Alex Goldmark: And we've had our share of after work drinks together, which is why I brought my whole little red cheek issue to you, only to be shot down.

Dan Pashman: That's right. So we have a long history together. We history of drinking together. But let's not get too warm an fuzzy here, Alex, because we do have to maintain a...a...

Alex Goldmark: Journalistic riguer?

Dan Pashman: I was gonna say, pretend heated rivalry.

[LAUGHING]

Dan Pashman: Speaking of which...

[PAPER SOUND EFFECT]

Dan Pashman: Here it is, Alex. That's an authentic paper sound effect, which mean, I'm about to read a law to you.

Alex Goldmark: Bring it on.

Dan Pashman: All right, this is title 27, section 5.22 of the Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms Code. This is the code, Alex, that aspiring vodka magnates read to their children at bedtime.

Alex Goldmark: Sound very intimidating.

Dan Pashman: It says that vodka must be distilled or treated until it is, “without distinctive character, aroma, taste, or color”.

Alex Goldmark: OK, but vodka has a taste...

Dan Pashman: But it has no distinctive taste.

Alex Goldmark: OK. Go on.

Dan Pashman: Like if you are making bourbon, you are going crazy trying to create a unique flavor so that your product will stand out, right? Like you're gonna age it in certain barrels for a certain amount of time or whatever.

Alex Goldmark: Right. And that's how it is smokey, or peaty, or other ones that I, actually, don't know.

Dan Pashman: Exactly.

Alex Goldmark: But I've heard.

Dan Pashman: Right, right. But if you’re making vodka, there is very little you are allowed to do to make it taste different.

Alex Goldmark: OK.

Dan Pashman: If you add sugar or fruit or something, then it becomes flavored vodka, which the law puts in a whole other category that's not traditional vodka. It’s essentially pure alcohol, just watered added that it doesn’t kill you. The word vodka comes from the Russian and Polish words for water. And the law today reflects that history. To call something vodka, you have to make an industrial grade pure alcohol first, like the stuff you would put in adhesives, or fragrances, or detergents. And then, take that and all you do is add water and you got vodka.

Alex Goldmark: That...ugh....that doesn't sound right.

Dan Pashman: All right, look. To figure out if there’s a difference between fancy and cheap vodka, let’s just start off by finding someone to show us how vodka is made.

Alex Goldmark: Makes sense.

Dan Pashman: All right. Someone who can show us how it all works standing right in front of their vodka making machines.

[UP DISTILLERY SOUND]

Ronak Parikh Hey there.

Dan Pashman: Hey, How are ya?

Ronak Parikh Good!

Alex Goldmark: How's it going?

Ronak Parikh Good!

Dan Pashman: This is Ronak Parikh, he’s one of the guys who runs Industry City Distillery in Brooklyn. The company got an unlikely start, when it’s founder was doing an experiment with aquaponics. Aquaponics is a system, where you raise fish in tanks and use their waste to feed plants you’re growing in the water.

Ronak Parikh And if you imagine plant life living with fish life, what you need to do is you introduce CO2, artificially, to that system. So we looked at natural ways to find CO2. One of those ways that you find CO2 is...fermentation. The other prime product of fermentation was alcohol. OK, well what can you do with the alcohol? The alcohol kind of became its own business.

Alex Goldmark: You're the founder of this company was just playing with aquaponics for fun and accidentally made vodka?

[LAUGHING]

Ronak Parikh Accidentally came across alcohol and spirits and looked at various ways of monetizing as this spirit that was coming off of was at the time tasty. that was coming off was really God damn tasty.

Dan Pashman: In those early, heady aquaponics days, Ronak hadn’t joined Industry City, yet. He was in business school, and had his own side project.

Ronak Parikh We had a copper still, working off of a stove. We were making—you know a friend of mine were making gins.

Adam Goldmark: And you just made gin like for fun with your friends?

Ronak Parikh Yeah. Exactly, they were great little things I just like to experiment with, um making various flavors. I think long term, I wanted to get into the business of making a brand, making the alcohol but at that time it was just kind of recipe building and just flavor creations, which is really fun.

Dan Pashman: Eventually, Ronak came to Industry City Distillery, and now he’s living the dream.

Alex Goldmark: He takes us down a long cluttered hallway, past a bar, and unlocks a big metal door.

Ronak Parikh You're entering our still room now.

Alex Goldmark: There are like clear jugs all around. There's this one machine that looks kind of like where you'd do to flip a circuit breaker to turn the power back on with some tubes coming out of it. Another one looks like an angry washing machine. And the whole room is kinda cramped, smaller than a dorm room.

Alex Goldmark: Yeah, I mean there's like enough room for maybe two or three people to be working. Basically, that's it.

Ronak Parikh Yeah, which is about our team.

Dan Pashman: So Ronak explained how to make vodka in a nutshell. First off, don't make it in a nutshell because that's very small. It's really a straightforward science. You combine sugar and yeast. The yeast eats the sugar and poops out alcohol.

Ronak Parikh Pooping alcohol.

Dan Pashman: It poops—right. So it's the yeast's waste product is what makes us drunk. Did you know that, Alex?

Alex Goldmark: That's news to me.

Ronak Parikh One man's trash is another man's treasure.

Dan Pashman: That's right. So when you get drunk, you're essentially poisoning yourself with yeast poop to forget about problems.

Ronak Parikh There you go.

Dan Pashman: And when it comes to what sugars you can use, the yeast isn’t picky. Neither are the standards for vodka. Like for instance, Alex, tequila has to be made with agave for it to be tequila. Whisky, it has to be corn or grain. But with vodka…

Ronak Parikh Really anything can make vodka. Sugar...exactly.

Dan Pashman: A Kit Kat?

Ronak Parikh Kit Kat...Kit Kat has sugar in it? I can ferment it and therefore distill it.

Dan Pashman: So after fermentation, you’ve got this vat of alcohol but it’s also filled with the leftover raw materials, the sugar and yeast and junk. You got to separate the alcohol. So you heat the mixture just to the point where the alcohol turns to steam and rises up.

Dan Pashman: So it goes up?

Ronak Parikh It rises like a gas up and there’s a condenser coil at that top filled with cold water. That's gonna condense it back to a liquor. We're dealing with gases. I gotta get it back to a liquid state in order to make it potable, so you can forget about your problems.

Dan Pashman: You do that a few times and you end up with basically pure alcohol. And every vodka, Alex, no matter how cheap, has to be distilled to that point.

Alex Goldmark: So these machines here, the main purpose of them is to remove flavor and scent and any other characteristic except for alcohol.

Ronak Parikh Exactly. Now alcohol chemical constituents of alcohol esters, they will create flavors. But in the case of vodka they will not be related to its raw material. By definition, that is the case. So if you ever see packaging that states, "Ah, this vodka is made with Northwest Pacific grains kissed by the Colorado rapids," that's all marketing bullshit. When it comes to vodka, your raw material cannot influence final flavor.

Dan Pashman: Ronak, are you ready for the lightning round?

Ronak Parikh Sure.

Dan Pashman: I’m gonna say a claim, a term, that I've seen on a vodka, not yours. And I want you to tell me what it means and whether it actually makes a difference.

Ronak Parikh OK. I like this.

Dan Pashman: All right. Here we go. Filtered through champagne limestone.

Ronak Parikh: [LAUGHS]

Dan Pashman: That sounds fancy. -

Ronak Parikh That does sound fancy, doesn't it? That really—now, what the heck does filtering though—what is champagne limestone versus limestone, would be my first question. And then I would also ask, what type of chemical reaction is happening when you filter through limestone. I think what were trying to do here when we do any filtration is we want to deodorize, we want to mask, that tells—whenever I hear of a distillery or brand doing that, they're trying to hide something. They're not trying to add. They're adding something to hide something. Why?

Dan Pashman: Charcoal filtered.

Ronak Parikh That's typically what you see in a Brita water filter. It acts like a deodorizer. You're removing a scent. Does that matter? Sure, it matters as far as deodorizing some nasty odors that would ordinarily come and reach your nose and your palette but again, you're masking something there.

Dan Pashman: Crafted in a an old-fashioned pot still.

Ronak Parikh Yeah. So pot stills have been used for sometime, for hundreds of years, probably since the beginning, and there is something about honoring age-old techniques. I think that's really important honoring age-old techniques when you are the—people have been doing for ages. If you're a finance guy that just left to open up your own distillery and you're starting new work on a pot still? I really don't know what that means. How—do you really know? Do you have the know-how and the history and the support network to really understand how that pot still works? Pot still are not the most efficient at distillation. Period. Glass and stainless steel, gentleman, these are two inventions, two discoveries mades by human that are really, really important and really, really good and efficient at distilling and making spirits.

Dan Pashman: So again, Alex, the raw material doesn’t matter to the final flavor. There is no flavor.

Alex Goldmark: But he did say, how you treat that raw material does affect what’s in the vodka. That’s because there are three stages of distilling.

Ronak Parikh Three categories; Heads, hearts and tails.

Alex Goldmark: Heads, hearts, and tails. OK. Ronak explained that when you start to heat the alcohol to distill it, the first part of the steam that comes up before anything else. That part is called the heads. That part is not supposed to be for drinking.

Ronak Parikh It's the stuff that can contain methanol. The stuff that moonshiners will get in trouble with going blind even being fatally, fatally hurt by it. You don't want to drink your heads you want to remove that.

Alex Goldmark: And then the next part, that's the good stuff, the hearts. So the stuff that Ronak wants to keep. That is the vapor in the middle. And then…

Ronak Parikh The last part is your tails. OK. That's the stuff that's potable but stuff that's been in our industry we've known to give you hangovers. It can create some nasty smells, some aromas.

Dan Pashman: So in theory, isolate the hearts, get rid of the heads and tails. And then the vodka runs through the still a second time, you start with only the hearts and then isolate the hearts of the hearts. So if a vodka is distilled six times, that should mean it’s only the very best part. The hearts of the hearts of the hearts of the—well, you get the idea.

Alex Goldmark: But Ronak says that if you wanted to make a super cheap vodka, you would just leave in extra tails through each run of the still. And then you just get more product to sell. The best vodkas, the ones that are sticklers for quality, they take just the hearts. So there is a difference, Dan.

Dan Pashman: Maybe. Hey, look. I like Ronak. He seems like a great guy. But remember, Ronak is also selling vodka for $40 a bottle. So I don’t think he’s gonna say that his is just the same as the $10 stuff on the bottom shelf.

Alex Goldmark: But Ronak did tell us one other interesting thing. Remember how he was one of the only distillers who we called up, who actually said, "Yeah, sure come on over. Take a look around."

Dan Pashman: Yup, yup. That's true.

Alex Goldmark: He says that’s because a lot of labels don’t distill their own alcohol. They buy it in bulk from somebody else.

Ronak Parikh Very often—this is not just vodka. Whisky, is especially, this is the case in America, where there's just a very few producers but a lot of brands. Right? So the distills all coming from one location. Whenever I see five-times distilled, six-times distilled? This is a very common number I see in our industry and that tells me, oh, yeah. There are some pretty big commercial manufacturers that are manufacturing this, doing five-times distilled, and selling that off to other distilleries who then don't distill it, who don't do anything other than add add water to it, slap a label on it, and call it, whatever vodka.

Dan Pashman: And that seems so weird to me because with every one of these vodkas, we hear this fairy tale about how the craft copper still blah, blah, blah, you know...

Alex Goldmark: Kissed by the Colorado rapids?

Dan Pashman: Exactly. Yeah. But I set out to find out how bulk buying works. And it's true. There's this one company that's huge, like everyone in the liquor industry knows them, Ultra Pure. They say they have the largest selection of bulk alcohol in the world. They sell, basically, pure alcohol like vodka concentrate. It's a base. Lots of companies buy it and use it to make their own vodka brands. Some of the companies take the base and distill it further. They tweak it. They put their own spin on it. But Ultra Pure told me that the more price driven companies, they just take the base, add water and they're in business, they're selling vodka. So I called them up and I said, "Hey, can I get some of that vodka concentrate?" And they said, "Yeah, no problem. Samples are in the mail."

Alex Goldmark: I appreciate this. I like it. I am looking forward to our science experiment, but I do not see how a vodka concentrate from a warehouse is going to be better than Grey Goose.

Dan Pashman: Oh, yes, of course, Alex. The famous Grey Goose from France with the French flag on the bottle, from the vaunted tradition of....French vodka?

Alex Goldmark: I see what you're doing.

Dan Pashman: I mean, yeah, back of the Palace of Versailles, I hear that the vodka flowed all day and night.

Alex Goldmark: Just keep going. The stage is yours.

Dan Pashman: In fact, when you think of alcoholic beverages in France, is there any alcoholic beverage that would even cross your mind other than vodka? I think not.

Alex Goldmark: OK.

Dan Pashman: I mean, go to the cave paintings of Lascaux and you will see murals of vodka as far as the eye can see. It is the quintessentially French beverage.

Alex Goldmark: You are making your point well.

Dan Pashman: Let's get real, Alex. Grey Goose was invented in the nineties by a college dropout from Connecticut.

Matthew Lefkowitz: Sidney Frank. He is a classic American businessman. In almost a cliche, both in good ways and in bad ways. Like he came from nothing, poor. He went to Brown, but he only went to Brown for one year because he couldn't afford it.

Dan Pashman: This is Matthew Lefkowitz.

Matthew Lefkowitz: I'm a drink writer and the author of You Suck at Drinking.

Alex Goldmark: So how many drinks do you have a day on average?

Matthew Lefkowitz: Oh, well, I'm trying to come back. When I was at the height of my drink writing powers, uh—oh gosh, five to eight?

Alex Goldmark: We are such amateurs.

Dan Pashman: Anyway, Sidney Frank drops out of college, ends up marrying a woman from a wealthy family and her family business is...liquor. So he kind of slides into the liquor business sideways.

Matthew Lefkowitz: He doesn't love liquor, necessarily. He's just looking for niche products. And he stumbles on this bar where he sees these old German folks drinking Jägermeister, which at the time—this was in the eighties—was selling like 500 cases a year, like nothing, nothing at all.

Dan Pashman: So Sidney Frank buys the rights to import Jägermeister, which if you don't know it, it's a liquor that sort of herbal, tastes kind of like black licorice cough sirup.

Alex Goldmark: Which probably explains the low sales. And he buys it precisely because it isn't well-known. And it doesn't really do much beyond the old German man market for a while. But then he hears about students at Louisiana State University actually liking Jägermeister. There's an article in the local paper that says all the kids know this is what you drink when you want to get drunk.

Matthew Lefkowitz: One of them described it as liquid Valium, and that was what kicked off—he was like, college kids. And with Jägermeister, he essentially invents all of the garbage that we may know about liquor companies and their marketing practices now. He, basically, invents them.

Dan Pashman: He sponsored parties, he butters up bartenders. He even sets up a team of scantily clad women to give away free shots.

Matthew Lefkowitz: Yep. Yeah, they're called the Jägerettes. That was a Sidney Frank special right there. So he had this kind of guerrilla marketing savvy. You know, he kind of didn't play by any of the normal rules.

Dan Pashman: So just to put a button on it Alex, in case it wasn't clear, Sidney Frank took a drink popular with old German men and turned it into the hottest drink for the party set on college campuses. And after he did that, he set his sights higher on vodka.

Alex Goldmark: And at the time, the fanciest vodka around was Absolut Vodka. It had a great marketing campaign, but by today's standards, it wasn't really an expensive bottle of vodka. And that's what Sidney Frank knows is his competition. But the thing he focuses on is not the taste of Absolut, of course, it is the price.

Matthew Lefkowitz: He, essentially, out of thin air goes, I want to make a vodka. So Absolut's charging 15, I'll charge 30. He didn't even have a product at this point.

Dan Pashman: But he already knows he's going to charge double. And in order to do that, he needs a product that screams luxury.

Matthew Lefkowitz: It's got to be the best. Everything....everything that is the best comes from France. So he goes to France and he looks around for distillers. He says, can you make vodka? He find somebody who says, yes, of course they can make vodka.

Alex Goldmark: And so he goes around to bars with his French vodka, making it seem special. He made a big deal that it was made of French wheat, all kinds of things designed to make Grey Goose seem different from other vodkas.

Matthew Lefkowitz: He would give them the bottle in these wooden boxes with straw inside and nicely packaged would be this large clear bottle with the frosted glass that when you put it up on the back bar, would catch whatever light was there and it would kind of glow.

Dan Pashman: It's not that he didn't care about taste at all, it's just that he didn't start there.

Matthew Lefkowitz: He did submit it to the BTI, which is the Beverage Tasting Institute, and it was awarded the best tasting vodka in the world in whatever, early 90s thing.

Dan Pashman: And he used that in his marketing a lot. Sidney Franks whole plan worked. Vodka is now the most popular liquor in America and he died a very rich man.

Alex Goldmark: He sold Grey Goose to Bacardi less than ten years after he started it for more than two billion dollars. And before you even start on this, Dan...

Dan Pashman: I'm tempted to start, Alex.

Alex Goldmark: I see how this whole story argues that that it's just marketing, that all vodkas are the same, that my allergy to cheap vodkas, that I genuinely feel, is all just in my head. But I think we should still test this as scientifically as we can.

Dan Pashman: I agree, Alex. And I got good news. Guess what just arrived in the mail, the vodka concentrate I ordered from Ultra Pure. Oh, boy.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Coming up, Alex and I attempt to make our own super premium vodka, then we send it to a lab to see how it measures up against Grey Goose. Plus, we'll check in at the bar to see how Alex's face is doing.

Dan Pashman: Did you bring an EpiPen?

Alex Goldmark: I don't even think I brought my inhaler.

Dan Pashman: Stick around.

MUSIC

+++BREAK+++

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Welcome back to The Sporkful, I'm Dan Pashman. We did something we have never done before in last week's show, we had our very own dating game. Using some extremely unscientific matchmaking, we sent two pairs of single Sporkful listeners on blind Zoom dates.

CLIP (DAN PASHMAN): Will, it seems like the two of you have very different perspectives on potatoes. Is this an issue?

CLIP (WILL): Ugh...maybe. It might be. Differences on opinion on potato texture is probably a bigger—more likely to be a deal breaker than a lot of other food stuffs.

Dan Pashman: Is the Spokful enough of a spark to ignite a grease fire of passion for two eaters? Or will these dates turn as cold as takeout fries? Check out last week's episode to find out.

Dan Pashman: Now back to today's show. And I'm here with my friend Alex Goldmark from Planet Money. And we are about to make our own vodka.

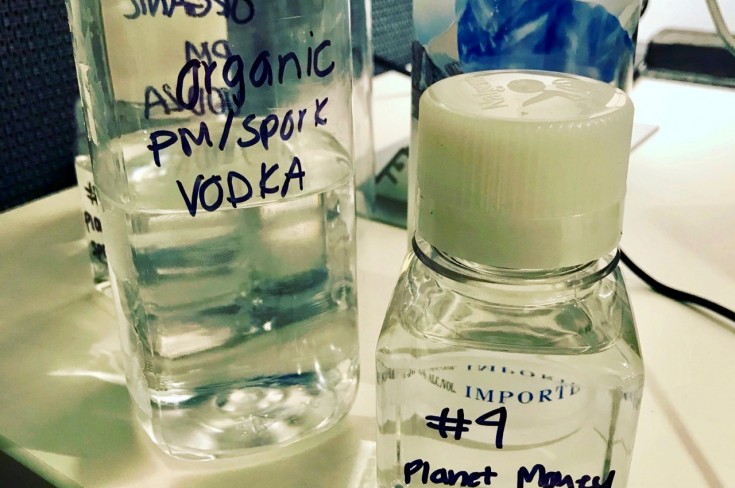

Dan Pashman: So, Alex, we got this vodka concentrate from Ultra Pure. And I picked out one in particular that I think you're going to be excited about.

Alex Goldmark: OK.

Dan Pashman: Ultra Pure sales of vodka concentrate made in France with French wheat four-times distilled.

Alex Goldmark: That sounds pretty good. I'd even say it sounds like it could be the best. The best that comes from France.

Dan Pashman: Exactly, Alex. That's right. Now, look, Ultra Pure told us they don't sell to Grey Goose, but they're clearly going for something similar here. I mean, there aren't that many vodka distilleries in France. We're not talking about wineries here. OK?

Alex Goldmark: And four-times distilled sounds good to me. Maybe even premium?

Dan Pashman: I would go so far as to call it super premium, Alex. And that's what we're going to do right now, we're going to make our own super premium vodka.

Dan Pashman: To clarify, Grey Goose is distilled only once, not four-times.

Alex Goldmark: I don't know, this looks like a like a travel shampoo bottle sized bottle with very clear white liquid in it. And they're wrapped in bubble wrap and tape. That's what we're taking off now.

Dan Pashman: Mm-hmm

Alex Goldmark: The labels look kind of homemade, though, Dan.

Dan Pashman: Yes, they look like they were printed on somebody's inkjet printer.

Alex Goldmark: Yeah, but not even with, like, the right alignment because alcohol sort of falls off the end...

Dan Pashman: Yeah, the label—yeah, they're cut off. Yeah.

Alex Goldmark: OK, well, our vodka company is off to a good start. We've got this very handy, fancy, highly scientific graduated cylinder that Planet Money owns, going back to our story on class action lawsuits.

Dan Pashman: Now, here comes the part of this entire story that I have most been dreading.

Alex Goldmark: What?

Dan Pashman: Math.

Dan Pashman: Grey Goose and most vodkas are 80 proof, which means 40 percent alcohol. But these bottles are not some even easy to work with number. They're 192 proof. So we got to bring those down to eighty proof by adding water.

Alex Goldmark: OK, it's 192 proof.

Dan Pashman: 40 percent...

Alex Goldmark: So if we have to make...

Dan Pashman: This is hard because...

Alex Goldmark: We have our intern here. Aviva?

Aviva Dekornfeld: Happy to be here.

Alex Goldmark: And she's got a calculator.

Dan Pashman: This is not 100 percent.

Alex Goldmark: I'm gonna say heads, math works.

Dan Pashman: If this was 100 percent vodka...

Alex Goldmark: All right, but then we need have 83.333

Dan Pashman: No, no, no. Oh, out of the 200...

Alex Goldmark: Kenny's the math major lessons. listen.

Dan Pashman: Let's get Kenny in here.

Alex Goldmark: We—Kenny's on deadline.

Dan Pashman: So Kenny, we heard you're a math major. We have a math question for you...

Kenny Malone: All right, how many milliliters is this?

Alex Goldmark: Well, we're gonna pour it into here.

Kenny Malone: OK, and what are you cutting it with again?

Alex Goldmark: Water.

Kenny Malone: Water.

Alex Goldmark: That purified water we got from the drugstore.

Kenny Malone: This isn't how you make vodka, is it?

[WATER POURING]

Dan Pashman: So we bottled our homemade French wheat vodka in a sterilized bottle and sent it to a lab because we wanted to see how it measures up. Thing is, we got to test it against something, right, Alex?

Alex Goldmark: Sure. Naturally.

Dan Pashman: So we also sent some Grey Goose in an unmarked bottle and we decided to send them some of the cheap stuff, the Alex special. Bottom shelf plastic bottle.

Alex Goldmark: We sent the whole thing to San Diego to a place called, White Labs. This is a whole lab where they test different types of alcohol.

Dan Pashman: Which I think Alex is something you and I have been doing for quite some time ourselves.

Alex Goldmark: Especially, this week for this episode.

Dan Pashman: That's right.

Dan Pashman: While the lab runs its tests, please enjoy this musical interlude.

[MUSICAL INTERLUDE]

Dan Pashman: To get our results, we called up Neva Parker. She's a vice president at White Labs.

Alex Goldmark: Did our samples...I'm just curious. Did they look professional? Did we look like a good vodka startup to you when you took them out?

Neva Parker: They absolutely did.

Alex Goldmark: Ahh. That's...that's gratifying.

Neva Parker: Yeah.

Dan Pashman: Neva ran our vodka samples through what they call a comprehensive spirits test. It measures different chemicals in the alcohol that people might be able to taste. Also, it test for chemicals that just shouldn't be there.

Alex Goldmark: We sent them three bottles with no labels, just a number on them. Number one was Grey Goose. Number two was our homemade French weed vodka. And number three was the bottom shelf plastic bottle vodka.

Dan Pashman: And Neva said one of the vodkas stood out because it had more of this one specific compound. It's called 1-Propranolol. And that's not a good thing. You want less of it in your vodka.

Neva Parker: Typically, when you taste 1-Propanol bottle, that's more of that harsher alcohol, kind of grainy alcohol compound.

Alex Goldmark: Yeah, like nail polish remover.

Dan Pashman: Right. So the vodka that has more of that stuff is not as good, according to this test.

Neva Parker: So it's possible that that shows that maybe this product wasn't distilled as many times or distilled to, you know, the same amount of purity as as the other two, which have lower levels.

Dan Pashman: Based on that information, Neva, which of these three vodkas would you suspect should be the cheapest, least desirable vodka?

Alex Goldmark: OK, remember, Grey Goose is number one. Our homemade vodka is number two. And the cheap stuff in a plastic bottle is number three.

Neva Parker: If I had to choose based on this analysis alone, I would say number one.

Alex Goldmark: And which would be the ultra luxury choice.

Neva Parker: Number three.

Alex Goldmark: Number three?

Dan Pashman: So based on...

Alex Goldmark: Wow.

Dan Pashman: Number three is the best vodka that money can buy of these three?

Alex Goldmark: To be clear, Neva said that all three of these vodkas, they had less of that bad stuff than anyone was going to be able to taste, but from what she could tell, the plastic bottle vodka seemed like the best. Grey Goose seemed like the cheapest. And our homemade vodka held its own against both of them.

Neva Parker: I mean, look at these. They all look very similar, as well.

Alex Goldmark: So would you say that ours is basically Grey Goose?

Neva Parker: Yes, I would.

Alex Goldmark: So we basically made Grey Goose.

Dan Pashman: Wow. [LAUGHS]

Dan Pashman: Well, we did talk to Grey Goose, their global brand ambassador, Joe McCanta, took issue with our test.

Joe Mccanta: Obviously, our product was decanted into another bottle. And when that happened, it kind of compromises our understanding of any testing that's done on the product afterwards.

Dan Pashman: He also argued that the odorless, tasteless law is more about distinguishing true vodka from vodkas that have stuff like fruit and sugar added. Pure vodka is its own category.

Joe Mccanta: Every vodka within the category will have its own characteristics, which would be largely attributed to the raw materials used to make the spirit or even the process used while distilling.

Alex Goldmark: One other thing that Neva told us about the vodkas that she tested, and I especially liked this part. Even if you can't taste the difference, trace amounts of any compound in the vodka you're drinking could be enough to set off an allergy, like maybe making your face turn red when you're drinking cheap vodka.

Dan Pashman: But the bottom line for me, science shows that if you don't have an allergy, all vodkas are pretty much the same.

Alex Goldmark: But if you do, there is one last test.

Dan Pashman: All right, Alex, you've moved on to drink number two. How are you feeling?

Alex Goldmark: I, actually, do feel the redness coming on. You're telling me I don't have it?

Dan Pashman: I mean, look, Alex. You've convinced me. I think what we have learned here today is that the differences between cheap and expensive vodka may not be testable for most people, maybe not even for you, but that your delicate constitution may be sensitive to them on the inside.

[LAUGHING]

Alex Goldmark: That was polite way of saying a lot of mean things. But I appreciate that. [LAUGHS] And I will take it.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Alex never did turn red that night. He can't say why I was a little red.

Alex Goldmark: I was a little red. I was a little red.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Alex Goldmark, my friend from Planet Money, you know, I always meant to take economics in college, but it always meant Friday mornings at 9:30 a.m. and so I refused to take it. And I figured that I would pick up economics, you know, just as I went through life. And most of what I know now, I've learned from listening to Planet Money because it's the show that's for people like me, who don't actually understand it intuitively.

Alex Goldmark: We try to have fun while talking about serious economic topics.

Dan Pashman: Well, Alex, here's to many more good times drinking sometimes for podcast, sometimes just for fun. Take it easy.

Alex Goldmark: I look forward to it. Thanks a lot, Dan.

Dan Pashman: I just got two words. Mission ImPASTable. The biggest, craziest thing we have ever done on this show. It launches in one week. While you wait for that one, check out last week's Dating Game episode. It's not like anything we've ever done, and I think you're going to love it.