Every other Friday, we reach into our deep freezer and reheat an episode to serve up to you. We're calling these our Reheats. If you have a show you want reheated, send us an email or voice memo at hello@sporkful.com, and include your name, your location, which episode, and why.

How do parents who adopt kids from other countries use food to connect their children to their birthplace? And what happens when those kids grow up and feel like it wasn't enough?

This episode originally aired on July 31, 2017. It was produced by Dan Pashman and Anne Saini, and edited by Dan Charles, with additional editing by Rebecca Carroll, Nicole Chung, and Peter Clowney. The Sporkful team now includes Dan Pashman, Emma Morgenstern, Andres O'Hara, Nora Ritchie, and Jared O'Connell. Publishing by Shantel Holder and transcription by Emily Nguyen.

Interstitial music in this episode from Black Label Music:

- "Pong" by Kenneth J. Brahmstedt

- "Can You Dig It" by Cullen Fitzpatrick

- "Minimialiminal" by Jack Ventimiglia

- "Hot Night" by Calvin Dashielle

- "Quiet Horizon" by Daniel Jensen

- "Legend" by Erick Anderson

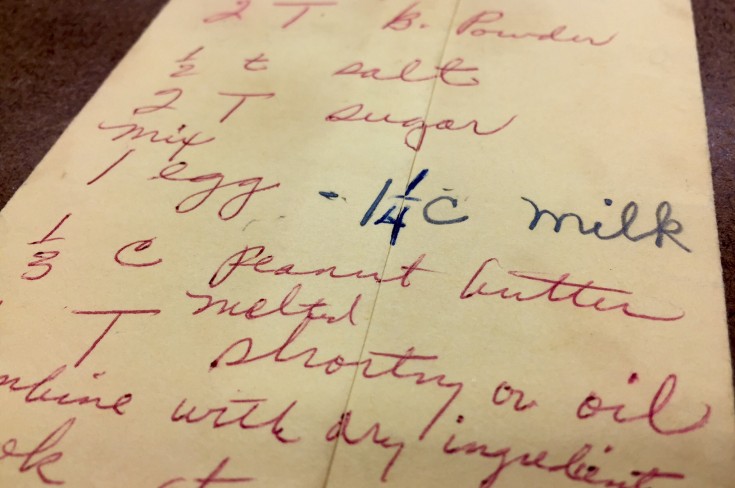

Photo courtesy of Amy Mihyang Ginther and Schuyler Swenson.

View Transcript

Dan Pashman: Hey! It's Dan here with another Reheat for you. Now, this one first aired in 2017 as part of a larger series called Your Mom’s Food — so it feels appropriate ahead of Mother’s Day. The overall series was about the complications that come up when we try to pass our food culture on from one generation to the next. The episode we’re sharing today was part one in the series, and it focuses on adoption. I’ll talk with parents who adopted kids from other countries about how they use food to connect their children to their culture of origin. And we’ll explore what happens when those kids grow up and feel like maybe it wasn’t enough. I hope you find it meaningful. If you have an episode you’d like us to pull out of the deep freezer of the Sporkful’s archives, send me a message at hello@sporkful.com. Thanks and enjoy this week's Reheat.

Mary Heffernan: So I made the doro wat, which is the chicken stew, and then I made — I’m gonna have to look at the names, because I just used the English names …

Dan Pashman: This is Mary Heffernan. We’re in her kitchen in suburban Long Island, where Mary’s cooking up Ethiopian food. Now, this isn’t the food she grew up eating. She cooks it because she has two adopted daughters who were born in Ethiopia.

Mary Heffernan: And then lastly, we’re gonna try to make an injera bread, which I’ve tried a couple of times and really haven’t been that successful, so I’ve done a little more research.

Dan Pashman: Mary does this a couple times a year. Her daughters are 11 and 13 now.

Dinknesh Heffernan: I’m Dinknesh.

Tikdem Heffernan: And I’m Tikdem.

Dan Pashman: And you are sisters.

Dinknesh Heffernan: Yeah

Tikdem Heffernan: Mm-hmm.

Dan Pashman: What’s going on today? What is this event? Tell me about it.

Tikdem Heffernan: Well, like once a month or so, we have some of our African friends come over, and it’s just, like, a time for our parents and us to, like, get together since, like, we’ve gone through the same things.

Dan Pashman: Like what?

MUSIC

Tikdem Heffernan: Like we’ve all been adopted, and all of our parents are single women, so — yeah.

Dan Pashman: What do you look forward to about these get-togethers?

Dinknesh Heffernan: Food. I like the food.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: This is The Sporkful, it’s not for foodies, it’s for eaters. I’m Dan Pashman. Each week on our show we obsess about food to learn more about people. On the day I visited Mary Heffernan’s house on Long Island, there were four families getting together — all single moms, all children adopted from Ethiopia. Earlier this year, Ethiopia actually suspended adoptions because of widespread issues with fraud. But for a while, Ethiopia was the only country that would allow single parents to adopt. At Mary’s house, there were six kids ranging in age from 5 to 13.

Dan Pashman: So what is this — the recipe for? What are you guys making right now?

Mary Heffernan: Misir wat.

Tikdem Heffernan: Misir wat.

Mary Heffernan: Which is Ethiopian red lentils.

Dan Pashman: Okay.

[GROUP CHATTER]

Dan Pashman: Also on the menu – injera. Injera is an Ethiopian flatbread. It’s thin and soft and spongy. The flavor is sort of whole wheat sourdough, and it’s really hard to make it well. Your ratios and technique have to be just right.

[GROUP CHATTER]

Dan Pashman: Three of the four moms there were white, including Mary. One, who you’ll meet later, is Puerto Rican. Mary adopted her daughters 8 years ago, when Tikdem was 3, and Dinknesh was 4 ½. Mary grew up in a big family in Queens — four brothers, four sisters. That’s why she wanted to adopt siblings.

Mary Heffernan: I quickly learned — my sisters used to always call me, "Oh, my son is the smartest and he won this game..", and I used to think their kids were like the best kids in the world, you know? And then, of course, very shortly, I knew my kids are the best kids in the world.

[LAUGHING]

Mary Heffernan: I was like, I think my kids are the smartest, funniest, etc., so ...

Dan Pashman: Right. And what kind of food did you end up eating?

Mary Heffernan: [LAUGHS] We were just talking about that — not very good food.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Mary Heffernan: My mother is Irish and she had a tough life. She grew up in an orphanage, so she really never learned any kind of housekeeping stuff or cooking, so we really didn't learn it when we grew up.

Dan Pashman: Why was it important to you to incorporate Ethiopian food into your home?

Mary Heffernan: Well, I feel like even, not just the food, but all of the things to do with their culture is very important. I know, like in my family, you know, St. Patrick's Day — the corned beef and cabbage is a big thing. And growing up, we had all the traditional type of Irish foods. So I felt that that would really bring them together. They just did just a culture day and we made Ethiopian honey bread.

Dinknesh Heffernan: I wasn't really nervous about in the breads so much, but, like, my mom had printed out pictures of, like, African culture and, like, pictures of what it's like there. And I was just like, "I don't want to bring this in," I didn't want her to make it at all, but she still made it.

Dan Pashman: Why didn't you want your mom to bring in those pictures?

Dinknesh Heffernan: I don't know. I just ...

Tikdem Heffernan: Its just out there.

Dinknesh Heffernan: Yeah, I was just, like, there was this one picture, it was like — they, like stretch out their lips with piercings and stuff like that, and I, personally, would never do that. It just grosses me out too much. But, like, I don't know how the other kids would react to it and I didn't want to, like, face any negative reactions.

Dan Pashman: And how did — how was the Ethiopian honey bread received?

Dinknesh Heffernan: Well, I have this one friend, Katie, and she's just like, "You should bring in your honey bread." And I was just like, "I don't know want to make it. " And she was like, "Why? It was so good."

Dan Pashman: How did that make you feel?

Dinknesh Heffernan: It made me feel happy.

Dan Pashman: Do you think you would have felt that way if it was any food you had cooked that they liked? Or do you think it was special because it was Ethiopian food?

Dinknesh Heffernan: I think it was special because it was more like my personal — cause I was worried that I'd bring it in and everybody would be like, "Ew. Yuck, like what is this? What kind of bread is this?", but, like, just getting that reaction gave me joy and happiness that somebody had liked my food and also my culture's food.

Dan Pashman: Are there any other Ethiopian kids at your school?

Dinknesh Heffernan: No.

Tikdem Heffernan: No.

Dan Pashman: Are there any other Black kids?

Dinknesh Heffernan: There's ...

Tikdem Heffernan: Some.

Dinknesh Heffernan: One?

Tikdem Heffernan: Or two.

Dinknesh Heffernan: Well, there's, like, mixed kids.

Mary Heffernan: I've said to the girls, you know, one day, you're probably gonna yell at me because we don't live in a very mixed neighborhood, and I said, as you grow older, you may think I didn't do enough, you know, to help you. Sometimes, I feel like I'm neglectful in that part — more than just the Ethiopian part.

Dan Pashman: I noticed that, like, even in the common areas of your home [Mary Heffernan: Mm-hmm.] you have, like, a poster for an Ethiopian coffee company.

Mary Heffernan: Right.

Dan Pashman: And you have other — I don't know for sure if they're Ethiopian ...

Mary Heffernan: Right, right.

Dan Pashman: But you have paintings and pictures that have Black people in them.

Mary Heffernan: Right, right.

Dan Pashman: I suspect that was a conscious choice.

Mary Heffernan: Yes. Yeah, yeah. My — a lot of the pictures, my aunt found out of out a calendar. She found an old Ethiopian calendar, and she put it all together for me and we put it up. But yeah, I try to make a conscious choice. It's funny when the girls first came, I felt almost funny having pictures with white people. [LAUGHS] I was kind of taking those down and then I thought that's kind of silly. I just put, you know, both up — a little bit of everything.

Dan Pashman: When Mary began the adoption process, she assumed the kids she’d be adopting would be orphans. But as she got closer to finalizing things, she got a big surprise. Dinknesh and Tikdem’s birth mother was alive. And Mary met her when she went to Ethiopia for the adoption.

Mary Heffernan: When I spoke to their mother, I felt guilty that I was taking somebody's children, I think. The biggest promise was to send the letters and the pictures, but I also felt, you know, she gave me such a big gift that it was important for me to, you know, return that to her and to make sure that these girls really felt — you know, knew where they came from and appreciated it. It makes me very emotional. It was probably the most emotional thing I ever did was speaking to the birth mother because she was so — it was so traumatic for her.

MUSIC

Mary Heffernan: I felt like it was kind of a promise to her to make sure that I incorporated all this into their lives.

MUSIC

[GROUP CHATTER]

Dan Pashman: So can you kids tell me a little bit about what we're doing here?

Tikdem Heffernan: Pouring this batter?

Mary Heffernan: Yes.

Tikdem Heffernan: Onto the pan, so you can kind of heat the batter up ...

Dan Pashman: And what's the batter for?

Tikdem Heffernan: And it would make a type of ...

Dan Pashman: What are you making?

Tikdem Heffernan: Injera bread.

Kid: Yeah.

Dan Pashman: Have you guys done this before?

Tikdem Heffernan: I haven't.

Kid: I don't know. I think I forget.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS] So this is the first time for both of you guys, making injera.

Tikdem Heffernan: Probably, yeah.

Dan Pashman: Yeah?

Kid: Yeah.

Dan Pashman: While some of the kids worked in the kitchen with their parents, I talked to Yosef. He’s 8.

Dan Pashman: If I were to say to you, "Yoseph, what's your food?", describe Yosef's food to me. What kind of food would you say it is of any food in the world?

Yosef Gonzalez: I would say Ethiopian food and rice and beans with hot sauce.

Dan Pashman: How do you feel about your food?

Yosef Gonzalez: They taste great to me.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS] They taste great to me too.

Dan Pashman: Yosef lives in Queens with his mother, Margarita Gonzalez. She brought him to the U.S. when he was about 2. And at first, eating was a big struggle for him. He wasn’t used to the density and texture of a lot of typical American foods. Here’s Margarita:

Margarita Gonzalez: So, he's home for about four to six weeks, and I've giving him oatmeals and things trying increase slowly the density of the food, so that he can better deal with it. And my friend puts a post on Facebook that says her daughters were so happy, and she just got back the Ethiopian restaurant in Colorado, and la-la-la. And I thought, oh my god, what is wrong with me? Why didn't I pick up Ethiopian food him yet? And so I drive into the city, pick up a sample platter, bring it back home, and I open up the box, and his face lights up, and he jumped on top of me and he gave me a hug. And then he dove into the food, and I was just like, "[GASPS] I really dropped the ball," I really felt horrible with the way he just hugged me. The smell — as soon as I opened up the box.

Dan Pashman: So he definitely recognized that food.

Margarita Gonzalez: Oh, he did. He did, and he had a favorite, and he went to it. And I would say every two to three weeks, I would stock up and buy several dishes and leave them in the house and whatnot. And so he had his favorite dish, very spicy. I would go to the restaurant and they would warn me, they were like, "No, no, no misir — very hot." I'm like, "I know." And they were like, "Don't let the baby ...", and I'm like, "No, it's for the baby."

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Margarita Gonzalez: It's not for me. I can't mess with that. That is way out of my league.

Dan Pashman: Right. [LAUGHS]

Yosef Gonzalez: I refuse to eat anything without hot sauce.

Dan Pashman: Really? What's your favorite kind of hot sauce?

Yosef Gonzalez: I would say Tabasco sauce.

Dan Pashman: Okay.

Dan Pashman: This is Yosef again.

Yosef Gonzalez: You know, Beyonce made a song about hot sauce in the bag?

Dan Pashman: Yes.

Yosef Gonzalez: I liked hot sauce before that.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Yosef Gonzalez: And my mom used to carry hot sauce in her bag before that.

Dan Pashman: So before Beyonce made it cool, you and your mom knew about hot sauce?

Yosef Gonzalez: Yes.

Dan Pashman: Yosef’s mom, Margarita, doesn’t cook Ethiopian food at home — they go out for that. Traditionally, Ethiopian food is served with injera, that’s the spongy flatbread you heard the kids making earlier. You pinch off a piece of injera and use it to grab the lentils or chicken, or whatever it is, with your hands, then you pop it in your mouth. In other words, silverware is not usually involved. So when Yosef went to an Ethiopian restaurant that had spoons on the table, he noticed.

Yosef Gonzalez: Like once we went to a restaurant, and we were using spoons. I was like, "This isn't Ethiopian food! You're supposed to use your hands!" I was like, "This is a disgrace to Ethiopian food."

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Yosef Gonzalez: I didn't tell that to the workers. I was like ...

Dan Pashman: Okay. [LAUGHS] But that's what you were thinking?

Yosef Gonzalez: Yeah, I told my mom.

Margarita Gonzalez: I was proud of him! I was very proud that he was able to identify, you know, true Ethiopian food and that he had such a sense of pride. Like, he really was really upset and refused to eat anything that day because there were forks there and the food was a fusion, and he was like, nope. I'm not having it. This is not what it's supposed to look like, taste like, smell like — I'm out.

Dan Pashman: So now, you're Puerto Rican.

Margarita Gonzalez: Yes.

Dan Pashman: And I know that Yoseph has a strong affinity for rice and beans ...

Margarita Gonzalez: He's a big fan.

Dan Pashman: As he told me! [LAUGHS] But I wonder if you went to — went out for Puerto Rican food, and if there was something in a restaurant that was equally inauthentic ...

Margarita Gonzalez: Mm-hmm.

Dan Pashman: Would he take so much umbrage?

Margarita Gonzalez: No. I don't think he would. But I think that he does defend Puerto Rico or he would have pride in that identity, but it is secondary.

Dan Pashman: I asked Margarita why it was important to her to keep Yosef so connected to Ethiopian culture.

Margarita Gonzalez: That comes from asking as many adult adoptees, especially international adoptees, that I could get my hands on — or the big thing that I heard over and over again was them complaining about having their childhoods whitewashed. And I guess, in my case, it would be Brown-washed. Right? Puerto Rican? [LAUGHS]

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Margarita Gonzalez: That's not fair. You know, my son has a different culture, he has a different homeland, he had a life before he met me. I just thought it would be a huge disservice to just be like, last name is Gonzalez now. Keep it moving.

Dan Pashman: Right. [LAUGHS]

Margarita Gonzalez: And don't worry about it. You'll blend in. I got cousins that look just like you.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

[GROUP CHATTER]

Dan Pashman: All right, how's the feast going?

Tikdem Heffernan: Yeah! That looks like real injera.

[GROUP CHATTER]

Margarita Gonzalez: He doesn't have the language, and he doesn't have the every day, but there is something that he still has from where his family's from.

Mary Heffernan: ... before actually eating it.

Dan Pashman: What's the review of the injera, Mary?

Mary Heffernan: Everybody is actually eating it, so we're working towards a better recipe. At least it's progress.

Dan Pashman: Progress. Yeah.

Mary Heffernan: But it definitely is progress.

Dan Pashman: Yosef — wait, finish chewing.

[LAUGHING]

Margarita Gonzalez: We have contact with the birth family and that's one of the things he's asked the translator, "What's my dad's favorite dish? Does he like spicy?"

Yosef Gonzalez: I think it's great and it's one of the best I've ever tasted.

[CHEERING]

Margarita Gonzalez: I can't give him, you know, in-depth Ethiopian culture in my home. I just can't. And so, you know, what little anchoring that I can give him, is what I try to do. But I am very, very well aware of the fact that it is a superficial connection.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: So what happens when adopted kids, who’ve been raised with this kind of connection to their birthplace, grow up and decide they want more? Coming up, we’ll hear the stories of two adult Korean adoptees:

CLIP (SCHUYLER SWENSON): Oh, I'm finally in this country where I was born, and everyone around me looks like me, and there's all this amazing food to be had and it looks beautiful, and I can't figure out how to just do the most basic thing of feeding myself.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Stick around.

MUSIC

+++BREAK+++

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Welcome back to The Sporkful, I’m Dan Pashman. And hey, want to watch me walking my dog while ranting about some food related issue that's on my mind? Want to see what I'm cooking? Want to see what I'm eating? The best way to do that is to follow me on Instagram. My kids make occasional appearances. There's a lot of fun to be had. So please follow me on Instagram @TheSporkful. Again, that's @TheSporkful. Thanks! Now, back to this week's Reheat.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: As Margarita said, the connection her son Yosef has to Ethiopian culture is very positive, but it’s also superficial. Now, we’re going to hear the stories of two adult Korean adoptees who had a similar feeling about their childhoods. And when they got older, the desire to connect with their roots more deeply led them to move back to Korea and even to try to find their birth parents. But before we get to those stories, we need a little context.

Dan Pashman: Korean adoption in the U.S. really started taking off in the '50s, after the Korean War. Back then, it was mostly mixed-race kids whose fathers were American soldiers. As South Korea recovered from the war and industrialized, more adoption agencies sprung up here and there. In the '60s and '70s, the children were fully Korean, and it was big business. By 1985, there were an average of 24 children leaving South Korea every day. Over the course of 60 years, it was the largest adoption exodus from one country in history.

Dan Pashman: Schuyler Swenson was part of that diaspora. She was born in South Korea in '87, adopted as a baby by a white family in the U.S., and grew up in a pretty white area of Denver. Most of her exposure to Korean food and culture came once a year.

Schuyler Swensen: There were these culture camps, they were called, and they were in the mountains, a week-long, and they were specifically for families with kids who were adopted from Korea. And they were a way to kind of introduce adopted families to Korean culture. And so myself and my brother, who's also adopted from Korea, and our parents — we'd go, we'd camp, and there'd be different workshops and different kinds of activities that really were the foundation of our knowledge of Korean culture. You know, it ranged from building, like, Korean kites as a kid, like toys, to eating kimchee, probably for the first time.

Dan Pashman: So when you had those first experiences eating Korean food, how did it make you feel?

Schuyler Swensen: [LAUGHS] I just remember, like, you know, styrofoam plates with japchae and kimchee and bulgogi and, you know, very, like, sweet and kind of oily foods. I liked it. I think I enjoyed it, but ...

Dan Pashman: Did it make you feel more Korean to eat it?

Schuyler Swensen: I think I always sensed that, like, this — the food at that camp was dumbed down for, like, an American palette for more our white parents than for us. After camp, I didn't go home and think like, oh mom, we got to eat bulgogi now, like that was the one space in our lives that we kind of compartmentalized. We'd go to this camp in the mountains and that was where we were Korean for a little bit and that was where we had exposure to Korean food. And then once we left, that was kind of it.

Dan Pashman: And are these happy memories.

Schuyler Swensen: It was important for us then to see other families that looked like our family, and so I value that experience. And I think that we did have fun, but then by the time I was maybe in middle school and my parents would ask us if we wanted to go back, and we kind of said, "You know, we'd rather go to soccer camp." I think we resisted wanting to associate ourselves with, you know, this particular camp because it made us feel different or other. I think we prefer to do what our other white kid friends were doing.

Amy Mihung Ginther: I really enjoyed going to culture camp.

Dan Pashman: This is Amy Mee-hung Ginther. In many ways, her story is similar to Schuyler’s — born in Korea in the '80s, adopted by a white family in the U.S., raised in a mostly white town, summer trips to Korean culture camp. But her feelings about camp are different.

Amy Mihung Ginther: It was a place for me to spend time with friends. And as I got older, it was, oh, I can see these friends only during this time. So, it was a feeling of reunion with people. And I think at a young age, I had a sense that hanging out with this type of community meant less questions would be asked and I wouldn't have to go through this whole, like, oh, I'm adopted and this is what Korea is. There was this immediate understanding or collective understanding, and that was really nice.

Dan Pashman: Amy’s quick to add she understood the version of Korean culture she was getting was superficial. Her parents did incorporate Korean culture in other ways. When she was in kindergarten, she was getting a lot of questions about her background, and kids were picking on her. So her mom went to the principal and said, "We’d like to have an afternoon in Amy’s class where we talk about Korea and adoption and cook some Korean food." Amy and her mom brought in the ingredients for mandu — Korean dumplings.

Amy Mihung Ginther: We would have, like, Korean candies that we would get at the one Asian food store that was in upstate New York at that time. And the kids would learn, like, how to use chopsticks with marshmallows, and then we would make mandu, and they would all get to eat some it, so they were getting exposed to that.

Dan Pashman: Do you remember being nervous, that what if all the kids said your food was gross?

Amy Mihung Ginther: I don't have any memories of having that fear. I think I loved Korean food so much and I enjoyed these things. Maybe if I hadn't gone to culture camp — and I already knew there was this community of people who liked all this stuff already. Kids at that age can be pretty picky, but I definitely think that some kids really enjoyed it. And I think there's something really powerful about that feeling accepted when there's this thing that you can share with them and they don't reject.

Dan Pashman: It became an annual thing. Every year, Amy’s mom would come into class, and together they’d do a presentation on Korea and serve Korean food. Amy says over time, it helped.

Amy Mihung Ginther: I have memories of someone who hadn't been in my class asking me something and having other kids be like, "Oh, you don't Amy's adopted from Korea? Like .... [GROANS]", you know?

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Amy Mihung Ginther: And so, it really did build up this knowledge of across my classmates.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: So Amy had some exposure to Korean food and culture. She was very proud of it. But as she got older, she still had more questions than answers. Schuyler did, too.

Schuyler Swensen: I remember going to college and thinking, oh, great. This is a time for me to really understand who I am and figure out my Koreaness, Korean identity.

Dan Pashman: This is Schuyler again.

Schuyler Swensen: So I remember going to a Korean Students Association gathering and walking in and being like, "Wow, everybody looks like me." And immediately, people started speaking in Korean and I was like, "Wow, I am not — this is not for me." [LAUGHS] That first initial college experience also drove me to question, like, okay, well, I'm not white. I'm not Korean-American, I'm kind of, like, hybrid in the middle.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: When Schuyler graduated college, she made a big decision. She bought a one-way ticket to Seoul. She didn’t know how long she’d stay. But she knew she had to go. And when she got there, she was hungry.

Schuyler Swensen: Got off the plane with — I just had, like, a backpack with me and immediately, I was, like, great, I'm gonna get some bulgogi, some japchae — you know, I, like — my mind went immediately back to culture camp experiences. You know, like what something quick and easy I can get. And I went into this department store and in the basement they — in all department stores, most of them in Korea, there are like massive food courts.

[KOREAN FOOD COURT BACKGROUND]

Schuyler Swensen: And there's tons of people waiting in lines with trays, beautiful, elegant department store stalls with heaps of food that I had never seen before. There was like a fish market and a meat section and, you know, candy and everyone's rushing by me. I don't speak any Korean.

[KOREAN FOOD COURT BACKGROUND]

Schuyler Swensen: And no one seems to be responding to — there was like a weird number system. Like, you had to pick a ticket or something? And I couldn't figure out — I was too shy to ask in English how to get in line. I'm trying to think of a good metaphor, but it was like being — I know there's, like, a classic kind of cliche, like ...

Dan Pashman: It sounds like, like it's kind of being in a foreign country.

Schuyler Swensen: [LAUGHS] Yeah, exactly.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Schuyler Swensen: Yeah! It was probably just like that. So I think I panicked and then I left, and I went to a 711 around the corner.

[LAUGHING]

Schuyler Swensen: And I just, like, and sand — you know, a sandwich wrapped in plastic, cause that was the easiest thing to just, you know — and I think I also got a can of Pringles. [LAUGHING]

Dan Pashman: And as you at that sandwich and those Pringles, what were you thinking?

Schuyler Swensen: I definitely felt defeated. But also, this kind of, like, existential crisis of like, oh, I'm finally in this country where I was born and everyone around me looks like me. And there's all this amazing food to be had, and it looks beautiful, and I can't eat any of it. And I can't figure out how I can do just the most basic thing of feeding myself. And I definitely knew right then that my time in Korea was going to be a struggle.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: When Schuyler left for Korea, she didn’t know for sure whether she’d try to contact her birth parents. But after six months there, she decided to give it a shot. Her adoptive parents encouraged her to do it. So, the way it works is Schuyler requests a meeting through the adoption agency, and then writes a letter to her birth mother. The agency delivers the letter and then it’s up to the mother to decide if she wants to meet. Schuyler waited a month to hear back. Finally, she got the answer — her birth mother said yes. Then she had to wait another four days for the meeting …

Schuyler Swensen: I got an email that was like, "We found your family. Do you want to meet them on Friday?", and this was, like, a Monday. And I agreed and then just was an emotional mess from Monday til Friday. [LAUGHS] Like, it was something you just can't fully prepare for and it was ... It was pretty intense.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: They first met at the adoption agency, with a translator. Schuyler’s birth father and older sister also came. At that meeting, Schuyler found out she had a younger brother, too. So her birth parents had another kid after her that they kept. After talking for a while, they went out to a restaurant.

Schuyler Swensen: The adoption agency was, like, okay, bye, [LAUGHS] like, go be a family, and kind of released us into the world. And my parents and older sister took me to a restaurant. It was a Korean barbecue place around the corner ...

Dan Pashman: Do they speak any English?

Schuyler Swensen: No. My older sister spoke a little bit but very, very basic — as probably more — she knew more English than I knew Korean, but it wasn't like we could have profound conversation. It was, like, "What kind of Korean food do you like?", probably was, like, the first thing. And we had Korean barbecue, and I sat next to my mother, and she did the Korean mother thing of preparing a little bite of food for me and kind of, like, feeding me. I knew that was kind of, like, a thing that happened in Korean culture, but it seemed, like, way too intimate to be comfortable with at that moment. It was like, hey, like, I know technically you're my mother, but like, we just met. [LAUGHS] So ...

Dan Pashman: You mean, literally, put the food in your mouth ...

Schuyler Swensen: Yeah, yeah.

Dan Pashman: With her hand?

Schuyler Swensen: Mm-hmm.

Dan Pashman: It’s common for a Korean mother to hand feed her child, and in some families, it is done into adulthood, at least in a sort of symbolic way, in certain settings. So Schuyler says that despite some awkwardness, that first meeting went pretty well. She started spending more time with her family. But the language barrier made it tough to really connect. Sharing food was one of the few activities they could do together.

Dan Pashman: Amy, meanwhile, followed a similar path. After college, she moved to Korea and connected with her birth mother, who by then had split up with her birth father. After that first meeting, Amy visited her family in the more rural area where they lived.

Amy Mihung Ginther: They would get me McDonald's take-out for lunch, and I don't eat McDonald's in the States.

Dan Pashman: Right. [LAUGHS]

Amy Mihung Ginther: So I had to, like, accept it because I didn't want to reject something at that stage. I wasn't super close with them yet and didn't know how to negotiate that. So I would just eat it, but it was so weird, because I'm, like, in the middle of, like, a much more rural part of Korea, eating McDonald's for lunch ...

Dan Pashman: And how did that make you feel that that's what they brought you?

Amy Mihung Ginther: [LAUGHS] I think I understood — really best intentions and that they were bending over backwards to make me feel as comfortable as possible.

Dan Pashman: At one point early on, Amy’s birth mother also fed her by hand. For Amy, it was awkward, as you might expect, but it was also meaningful.

Amy Mihung Ginther: This is what we can do now. You know, we can't make up all of those years. There's no way, right? And so we can focus on what we can do now. And what that is is allowing her to feed me and her feeling good about that and feeling like there's some element of care and for me to accept that care.

Dan Pashman: Amy began calling her birth mother Oma, Korean for mom, and eating lots of her Oma’s cooking.

Amy Mihung Ginther: I think the biggest thing was my Oma's japchae, which is just the best.

Dan Pashman: Japchae is glass noodles made from sweet potatoes. They're stir-fried with soy sauce, sesame oil, sugar, spices, vegetables, and sometimes meat. Back in culture camp, it was Amy’s favorite. But her Oma’s japchae was on another level.

Amy Mihung Ginther: It really — it's just really fresh. Like I feel like the japchae I had in culture camp was made in massive quantities. You know, there's these glass noodles, right? And so if they are refrigerated or if they are out a bit, they start getting cloudy and, like, rubbery. And so, yeah, it was just really good and not mass-made for, like, 40 campers at a culture camp.

Dan Pashman: So there's this food that you had had a version of in the U.S. growing up that was one of your favorite Korean foods. Then you end up in Korea as an adult, eating a way better version of that [AMY MIHUNG GINTHER LAUGHS] but of that same dish [Amy Mihung Ginther: Yeah.] made by your Oma. In that moment, eating that food in Korea, like, when you then look back on the experience of eating that food in culture camp, how did it make you feel about that experience?

Amy Mihung Ginther: Yeah, I think it's a lot to reflect upon, in that it may have felt like it had legitimized my experience in culture camp. So this was, like, a thing that they did, that I thought that Koreans did because I had it growing up, but, like, this is happening. This is really happening in real life.

Dan Pashman: [LAUGHS]

Amy Mihung Ginther: This is a real person doing it.

Dan Pashman: Right. [LAUGHS]

Amy Mihung Ginther: I think it was just exciting to eat a thing that I already liked and knew what it was that my Oma makes and makes really well.

Dan Pashman: Schuyler connected with her birth mother’s home cooking too. Back in culture camp, the kimchi was syrupy and sweet. But at her mom’s house …

Schuyler Swensen: It was spicy. It, like, intense. It was kind of that, like, real Korean, not watered-down kimchi that I would hope for? [LAUGHS] I hate the word authentic, but I think that there was something kind of gritty and country about it that I really liked. And it wasn't like, oh wow, I'm wrapped in the arms of my biological mother [LAUGHS] eating her kimchi. It wasn't like this totally transcendent experience, but it was salty and spicy and kind of fishy, kind of raw, and I appreciated that a lot.

Dan Pashman: Both Schuyler and Amy came back from Korea with a much stronger connection to their roots. But figuring out their relationship to those roots ... that’s an ongoing process. There are some Korean adoptees who’ve gone back there and stayed. Others, like Schuyler’s adoptive brother, say they have no interest in going back at all.

Dan Pashman: Schuyler's got a group of friends in Brooklyn who are all Korean adoptees. They get together every so often and cook Korean dishes. In some ways, it’s an adult version of the Ethiopian kids making injera with their parents.

Schuyler Swensen: We had celebrated the Lunar New Year together and cooked mandu dumplings. Another event, we made kimchi together. We, like, rolled out a big white sheet on the floor and, like, all took our shoes off and bought, you know, the giant napa cabbage heads, and immersed them in these buckets of water and salt, and, you know, did all the steps of making as authentic as we can — the whole while, watching this YouTube series by this woman, Maanchi — I think is her name?

MUSIC

CLIP (MAANGCHI): Hi everybody! Today, we are going to learn how to make Korean traditional kimchi!

Dan Pashman: The woman’s name is actually Maangchi, and her YouTube cooking videos get millions of views.

CLIP (MAANGCHI): As you know, there are so many, hundreds of different kind of baechu-kimchi. This is going to be a very traditional ...

Schuyler Swensen: She is like this super cute glammed up Korean lady. She's fabulous. And she kind of walked us through how to make kimchi at home. And so, it was this kind of very millennial American moment watching a YouTube video about our ancient culture of origin [LAUGHING] of, like, how to make kimchi. So, yeah.

Dan Pashman: And how did you guys feel about that experience?

Schuyler Swensen: Oh, it was beautiful. I mean, it was so fun to be making ritual together that is a unique Korean American adoptee activity and teach ourselves — like, bring ourselves up in America as Korean Americans because our white parents maybe aren't able to do that for us. We fought for that. We, like, taught ourselves how to have an understanding of that part of our identity that was lost.

Dan Pashman: Do you think your adoptive parents understand that feeling?

Schuyler Swensen: I think they do. I think, as parents, you know, they are protective. They want what's best for their kids, and often, there is this kind of fairytale narrative of adoption that says it's this beautiful thing. Our family transcends cultural racial boundaries, and, you know, we are a happy family — and that's absolutely true. And I believe that and my parents believe that. What's often left out of the conversation is that adoption is also inextricably connected to trauma and loss. It's both things. And it was not until reaching adulthood and reconnecting with my biological family that I was conscious of that other half.

Dan Pashman: I asked Amy what advice she’d give to parents who’ve adopted kids from other cultures.

Amy Mihung Ginther: At the end of the day, for a parent to be engaging with food from the place that their kid has been adopted from is definitely better than not. But regardless of what they do, there is still some loss that they cannot even heal for that person. That's the journey that they have to take. I think what's the most helpful for adoptees is when parents acknowledge that they can only do so much.

MUSIC

Dan Pashman: Please make sure you subscribe to this show in Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you listen. That way you’ll never miss an episode, and it helps other people discover our show. So please hit subscribe right now. Or maybe in your app it’s favorite or like, just please do that thing. Thank you.

Dan Pashman: My thanks to Mary Heffernan, Margarita Gonzalez, Lauren McNally, and everyone at Mary’s house for their hospitality and delicious Ethiopian food. And thanks to our Korean adoptee guests. Amy Mihung Ginther teaches theater at the University of California Santa Cruz. Her one-woman show about exploring her identity is called Homeful. It debuts in September at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. And Schuyler Swensen is a producer on the radio show Studio 360.